I was poking around in some of the dusty, cobwebbed corners of the inter-net the other day when I came upon the story of David Ingram. The legend of David Ingram? The mystery? I don't know what to call it, but it's goddamn fascinating.

David Ingram was an Englishman who left his home country in 1567 with a couple hundred other guys in a fleet of five vessels on a slave-stealing mission to the Caribbean. Now, here are two generally-to-widely accepted facts about what happened next:

- After being attacked by the Spanish, Ingram and about a hundred other sailors were cast ashore at Tampico, Mexico - a town at the westernmost point of the Gulf of Mexico, two hundred miles south of what's now the Mexico/USA border.

- 11 months later, Ingram and two others of his original party were discovered by a French fishing vessel ... ON THE COAST OF NOVA SCOTIA. NOVA SCOTIA. IN CANADA.

And how, you and literally everyone else who has ever heard this story might ask, did these guys get from the middle of Mexico to the shores of Nova Scotia 3,000 miles away in 1568 (1568!) with no roads or boat or maps? They walked, of course. Something like this:

The journey boggles the mind, but no one has any evidence that those basic facts are untrue. Thirteen years after he was rescued and returned to England, Ingram told his story to a guy named Sir Humphrey Gilbert, and that testimony was then published by another guy named Richard Hakluyt in 1589 as part of his series on English exploration called

Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation. While I've searched the dark corners of the internet for Hakluyt's relation of Ingram's story, I can't find it (just the

still-interesting version of Hakluyt's Principal Navigations released in 1590).

The best article about Ingram's journey is "

The Longest Walk: David Ingram's Amazing Journey," published by Charlton Ogburn in American Heritage magazine in 1979. Odgen writes that Ingram's telling of the story to Gilbert was oddly short for such an amazing story, and was likely embellished by a combination of factors including Ingram's poor memory (it was thirteen years later, remember), his subsequent travels to Africa and South America, and the general English will to believe that there was a passage to Asia somewhere in the New World.

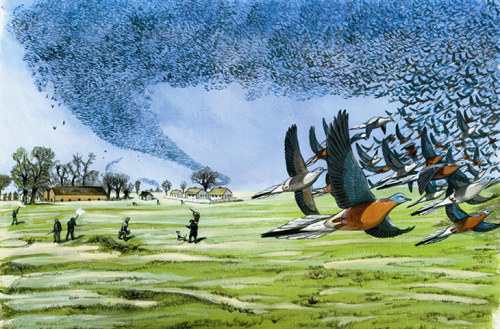

Ingram does make some interesting observations, though, observations that are recognized as the first English language descriptions of inland America. Ingram talks of huge Native American cities filled with silver and rubies, animals that sound like elephants, and, of course, birds. Birds! The first English-language descriptions of American land birds!

Ingram spoke of

"Guinie hennés which are tame Birds … as big as Geese, very blacke of colour," that were likely turkeys. He spoke of an "abundance of Russet Parrots" that, while initially puzzling, were likely Passenger Pigeons. Ingram described the flamingo - a bird "billed like a shovel" - though it's unclear where Ingram would have seen flamingos during his journey. [NOTE: smart commenters below have pointed out that this bird is much more likely to be a Roseate Spoonbill, not a flamingo.] Either flamingos were more commonly seen on the Mexican coast back then, or Ingram was confusing this tale with another of his eastern journeys.

Ingram also describes a "very strange Bird, thrise as big as an Eagle, very

beautifull to beholde … his head and thigh as big as a mans … His beake

and talents in proportion like Egles, but very huge and large." Huh? Ogburn and the ornithologist George E. Watson seem to think that this mystery bird could be some link to the "terror birds" found fossilized in Texas and Florida, but neither seem to actually believe that. Could be a Condor, somehow? A Golden Eagle (elsewhere, Ingram describes seeing "feathers in the haire of" Native Americans, from "a Byrde as bigge as a goose of russet collour"- likely one of the two American eagle species)? A crane? No idea.

Ingram also describes the Great Auk, a bird "which hunteth the Riuers neere unto the Hands: They

are of the shape and bignesse of a Goose but their wings are couered

with small yelowe feathers, and cannot flie: You may driue them before

you like sheepe: They are exceeding fatte and very delicate meate." Ingram went on to say that these Auks "have white heads, and therefore the Countrey men call them Penguins (which seemeth to be a Welsh name)." While no one is really sure what the white heads part is about, the use of the word "penguin" is believed to be one of the first ever uses of that word. [Note again: smart commenters below have other theories for this, the coolest and, I believe, most likely of which being the now-extinct Labrador Duck, in all its white-headed glory. Though, Ingram's yellow wing comment is still open to question.]

It's interesting that two of the handful of birds Ingram describes are now extinct. The ubiquitousness and lack of fear of Great Auks and Passenger Pigeons were their most noteworthy characteristics - and also what hastened their declines. America's earliest birds found a land that was much different than what we see now, and what many birders wouldn't give to recreate Ingram's walk!

[Note: I recognize that the "First American" in the title excludes Native Americans, the Spanish, and anyone else who was in America before Ingram. This is just the first English-language account that exists.]